Lafayette, LA – Inside almost every golfer lies an amateur course architect hoping for an opportunity to spring into action. What golfer doesn’t have the perfect idea for how to improve a hole on their favorite course, or spends downtime sketching hole designs? Building a golf course calls for physical labor, problem solving, and a talent for working with people from all different backgrounds. In 1923, Metairie presented builders with the ultimate challenge: severe drainage issues, stump removals, snakes, and of course, the heat. Thankfully for Metairie, Joseph Bartholomew was the perfect man for the job.

Seth Raynor designed Metairie Golf Club in the Golden Age of golf course design, and he entrusted Joe Bartholmew to carry out his vision. Plasticine models were employed to show Raynor's green designs in miniature form, so that the men responsible for building those designs would understand what Raynor wanted. In the Metairie CC centennial book, Michael Wolf gave Bartholmew the moniker the Builder of Metairie, and it certainly rings true.

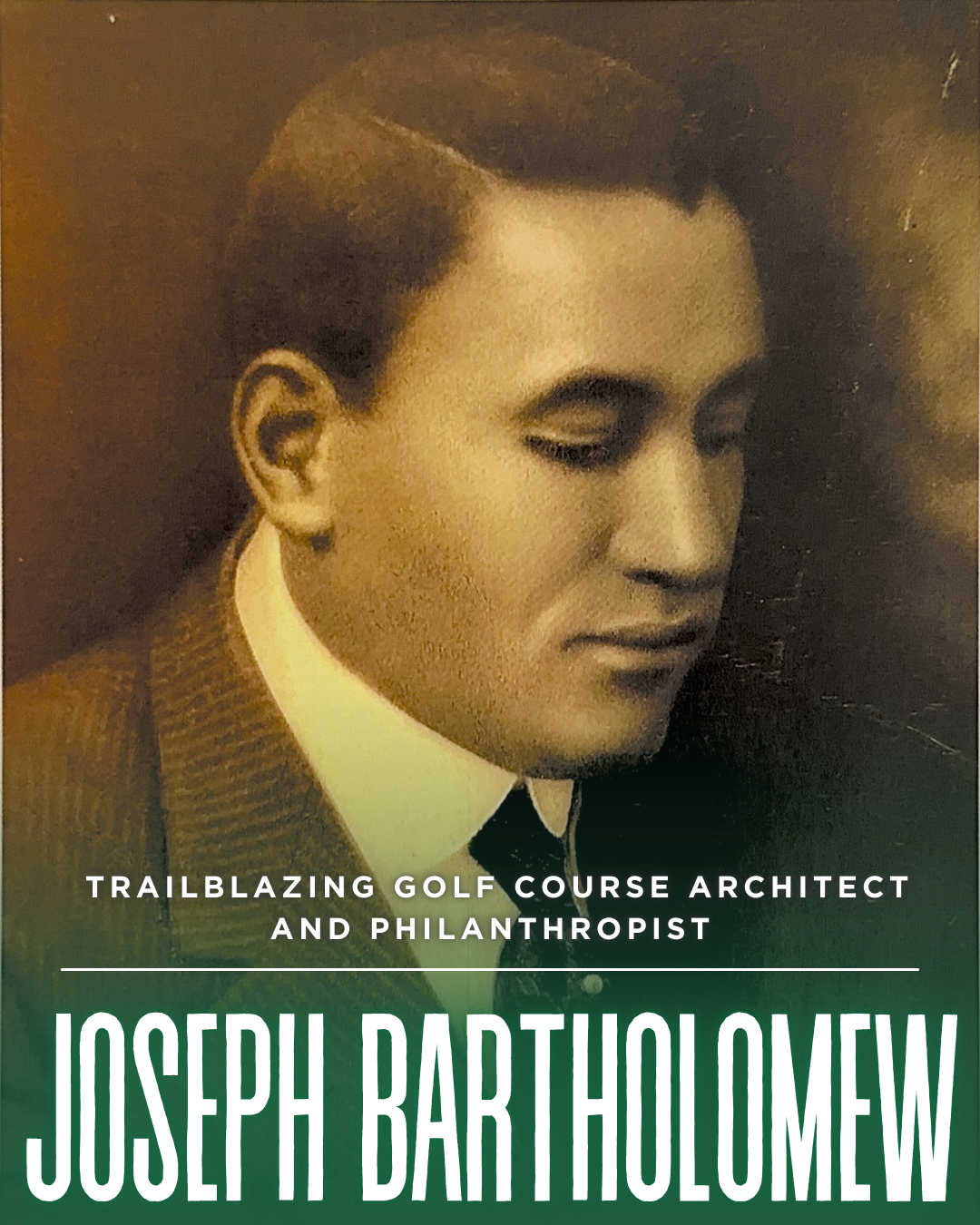

Bartholomew was born on August 1, 1890, at the corner of Cherokee and Ester streets in New Orleans. He began developing his business skills at a young age. By the age of seven, Bartholomew was working as a caddie at a nearby golf club, Audubon Golf Club, a private club at the time that leased land from the City of New Orleans. The job was a perfect fit for the seven-year-old, working for some of the city’s wealthiest businessmen, which appealed to his entrepreneurial spirit. During these early days, Bartholomew developed a lifelong love for the game due to the physical and mental challenges of golf.

By his teenage years, Bartholomew’s golf game and work ethic caught the eye of Audubon’s head professional, Fred McLeod, who offered him a job inside the shop building and repairing clubs. While working on and off the course, Bartholomew set a course record of 62 at Audubon and became a favorite instructor among members looking for lessons. His game was strong enough that the Audubon membership backed him in matches against barnstorming professionals.

By the late 1910s, there was increasing talk that Audubon’s lease would not be renewed so the City could take over the golf course for public play. New Orleans was experiencing significant population growth, and the city’s crowded citizens were demanding places to rest and relax. The members of Audubon Golf Club would soon need a new place to play, and Joe Bartholomew would soon have his next opportunity.

Two of Bartholomew’s grandsons shared memories of their grandfather during lunch with Michael Wolf at Metairie. They remembered him as a physically impressive man, standing 6-foot-2, with the build of someone accustomed to physical labor. Known to many as “Fess,” short for professor, Bartholomew was a devout Catholic who attended 6 a.m. Mass every Sunday at St. Joan of Arc Church on the corner of Burthe and Cambronne streets. His grandsons also recalled their grandfather’s sweet tooth, especially his love for orange pop sodas. In his later years, he smoked cigars, but not before cutting them in half to make them last longer. Most photos show Bartholomew as a well-dressed man, usually wearing a fedora, but that was about as far as his self-indulgences went. He continued purchasing used cars long after he had become a wealthy man.

After building Metairie Golf Club’s course, Bartholomew became the club’s first Head Professional as well as Head Greenskeeper. Just an abbreviated list of his responsibilities would have included giving lessons, making and repairing equipment, conducting tournaments, hiring and supervising a large staff of employees, training young caddies, managing budgets, and making crucial agronomic decisions. A young club like Metairie also required substantial investment in equipment and facilities while operating with relatively limited incoming capital. Praise for Bartholomew’s green thumb was universal. The course was in such good condition when Metairie hosted the 1928 State Amateur that the Louisiana Golf Association awarded Bartholomew a gold watch for his excellent work. Somehow, in the midst of this whirl of activity, Bartholomew also found time to maintain a golf game that still showed flashes of brilliance. One contemporary newspaper account reports him shooting in the mid-60s during a rare day off at Metairie.

After a decade of building and improving Metairie, Bartholomew took over greens-keeping duties at New Orleans Country Club in 1937. No documented reason exists for his move, but a likely factor was the pending construction of Airline Highway, which was expected to bisect Metairie’s golf course.

Bartholomew soon became involved in several successful business ventures. He had the foresight to reinvest his early paychecks into owning the very machines he would later use in his growing list of projects. With the reputation he earned from building Metairie, Joe’s excavation company became the go-to firm for a string of New Orleans mayors. He also continued to build golf courses, both public and private, throughout New Orleans and across the state of Louisiana.

Bartholomew was comfortable conducting business with businessmen and politicians of all races and backgrounds. While rare in 1930s New Orleans, this was perhaps less surprising given that he had interacted with the city’s elite since his earliest days as a caddie.

His grandsons fondly recalled spending every Christmas Day of their childhoods at parties hosted at Edgar Stern’s home. A 1999 Times-Picayune profile on Bartholomew includes several informative quotes from some of Joe’s lifelong friends.

“I don’t think he was conscious of racism in any way,” said his friend Henry Thomas. “He couldn’t play golf at City Park, but he never mentioned it.”

“He never mentioned it,” his daughter Ruth is quoted in the article. “Never talked about it. What we knew about segregation we found out from other people. We didn’t know segregation. We played with everyone in the neighborhood. No one segregated my father as an individual.”

The lives of Bartholomew, his family, and his friends were certainly affected by the systemic racism and prejudice that openly existed in New Orleans and throughout much of the country during this period. Sales literature from the era plainly stated that the Metryland development, the neighborhood surrounding Metairie Golf Club, would be for whites only. African Americans were not allowed to play at most golf courses during this time, including those built by Joe Bartholomew. Still, there is ample evidence that members of Metairie were fond of him. Bartholomew was allowed to play at Metairie during his 13 years as the club’s professional. His longtime friend Joe Dyer, once a caddie at Metairie, is quoted as saying they were also permitted to play at New Orleans Country Club on Tuesdays and Fridays with other club employees.

As Bartholomew’s business success continued to grow, his time playing golf reportedly declined. A growing family and multiple business projects filled his days. He was perfectly positioned to take advantage of the rapid expansion of manufacturing that occurred in New Orleans during World War II. Along with his construction and earth moving businesses, Bartholomew owned the Douglass Insurance Company, an ice cream factory in the Ninth Ward, and real estate holdings in several neighborhoods throughout the city. After Metairie, Bartholomew went on to build or rebuild City Park’s first and second courses, Pontchartrain Park, and courses in Covington, Hammond, Abita Springs, Algiers, and Baton Rouge. He also personally funded a seven-hole layout he built for his African-American friends in Harahan.

By the end of 1949, Forbes magazine estimated Bartholomew’s wealth at $500,000 — more than $6 million in today’s dollars. He was generous with that wealth, supporting both Dillard and Xavier University, supplying the limestone used to build the former Charity Hospital on Tulane Avenue, and donating a stained-glass window to Blessed Sacrament Church. Bartholomew was also an active member and early supporter of several prominent African-American social clubs in New Orleans.

On a personal level, Bartholomew was equally generous, perhaps overly so. His wealth attracted a steady stream of friends, neighbors, and strangers seeking small loans or handouts, and all who knew him recalled his inability to refuse anyone who asked for help.

Joseph Bartholomew died on October 12, 1971. A year later, he became the first African American inducted into the Greater New Orleans Sports Hall of Fame. In 1979, the city renamed Pontchartrain Park Golf Course in his honor, a fitting tribute to a man who, over the span of a lifetime, transformed golf in New Orleans.

Bartholomew was posthumously awarded the Louisiana Golf Association's Distinguished Service Award in 2007, which honors individuals who have contributed to the betterment of the game in Louisiana.

Written by Michael Wolf. Historical content and images provided by Metairie Country Club.

About the Louisiana Golf Association

The Louisiana Golf Association is a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting, preserving, and growing the game of golf across Louisiana. Founded in 1920, the LGA conducts state championships, provides USGA Handicap Index® services, and supports players of all ages through initiatives like the Louisiana Junior Golf Tour.

Media Contact:

Maili Bartz

Director of Marketing & Communications

maili@lgagolf.org